-

About Us

-

Library

-

What We Do

-

Latest

- Shop

Stoic Love – the Dos and Don’ts

December 22

We mostly talk about emotions in the context of Stoicism with the aim of managing them.

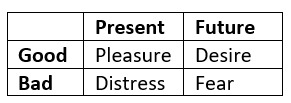

According to the ancient Stoics, these are to be approached with caution, be they positive or negative (as usually perceived), as exemplified below:

Instead, these should be replaced with joy, wish, and caution.

Perhaps we can see how some types of love have the power to bring all these emotions into one experience. While romantic love (at least in its modern interpretation) is not analysed extensively by the likes of Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and Epictetus, the concept of Stoic love, and in particular how it fits within the good life that as modern Stoics we strive towards, is important to reflect on.

When it comes to facets and applications of love, our predecessors had a very distinct classification system. They talked about love not as one emotional bundle of give and take wrapped under a culturally predetermined model, but as a range of experiences we can share with multiple individuals. These were, by and large:

Sexual desire (eros); platonic connection (philia); familial love (storge); mature love of long-term partnerships (pragma); playful love (ludus); obsessive love (mania); and perhaps closest to what a Stoic sage’s definition would be, agape – a form of unselfish, charitable, cosmic and transcendental form of love.

Without coercing one single individual to provide us with all these experiences, we are able to both extract things that benefit us, as well as represent various avenues for us to channel our own abilities to give and express ourselves in relation to another (or several others). Depending on where you are in the world, the notion that we need not expect for our partner to fulfill most of the above might sound unusual. The way most societies are structured in the 21st century differs in theory and in practice from the ancient Greek conception. Therefore without resorting to polyamory, it is one’s task when in a committed monogamous relationship to strike the balance between these interactions with their chosen partner.

As with other aspects of our lives, we might consider love through the lens of the cardinal virtues, and in this short piece I summarise some of the do’s and don’ts of modern Stoic love, as I have come to understand them, with a skew towards the romantic type (but feel free to extrapolate).

COURAGE

To start off, Stoic love does not operate well without continuous acts of courage. Loving courageously can mean a few things: the courage to expose your fears and insecurities, or own your mistakes and your limitations, regardless of the associated fears of rejection or admonishment; the courage for commitment and forgiveness; the courage to let go of a loved one, when holding on is unwise. This requires sustained attention and frequent reconfiguration of what virtuous love means within ever-evolving relationships.

Following on from A.C. Grayling’s take on courage that ‘it is hard to accept that to live is to lose, that to love is to lose, that trying to achieve anything of value is to lose – and that the only way to gain what matters is to accept these facts with courage’, a Stoic would view the link between loss and courage as natural and the former not as a negative, but merely a fact within any lived experience to be managed through resilience.

MEMENTO MORI

Mustering up ceaseless courage is easier when we remind ourselves that nothing lasts. While it is much easier, at least in the short run, to over-indulge in pleasurable moments by ignoring their impermanence, remembering that everything is temporary can alleviate any pain we might incur in the long run when those moments do pass:

“Regard everything that pleases you as if it were a flourishing plant; make the most of it while it is in leaf, for different plants at different seasons must fall and die.” – Seneca, Letter 104

The contemplation of death or more generally of departure can be a useful tool in loving Stoically. Such losses, whether through breakups or more impactful ways, can bring great grief amongst other strong emotions. So, before any of that happens, on a sunny day when you and your loved one are blissfully spending the day together, take a moment to envisage a world without them, for any subsequent day can bring that possibility into fruition. Sometimes a lost love is partly up to us, and sometimes it is not. We have to be prepared to purposefully accept both.

GIVING LOVE: ACCEPTANCE

Stoic love calls for accepting things, be they our partners themselves or characteristics of our dynamic with them, as they are. Two Stoic concepts which on the surface seem to contradict each other are relevant here. On one hand, if our goal as aspiring Stoics is to develop our character, and assuming our partner is directly or indirectly striving towards the same ideal, one of our roles is to support their character development. On the other hand, acceptance of what is, the nature of our partner and the entirety of who they are (things like their temperament, their personality, their spirit) is equally important. This equates to loving our fate, and that of our partner in our shared journey. Together, these thoughts render a Stoic love an experience whereby we observe what is, while nourishing what could be in our partners, without trying to coerce what is not up to us into existence.

Thus we should love with fortitude. When thinking of love of as an act of giving, we recognise that even though our efforts may sometimes be futile or unwanted, we are bettering and supporting another human through our capacity to show them care, affection, and understanding.

RECEIVING LOVE: INDIFFERENTS

When love, or more precisely, the feeling we derive when we perceive we are being loved, is deemed an indifferent (to our character), we realise we can live good lives with or without the presence of another (oftentimes arbitrary) person, no matter how strong an affiliation we think we have with them. Being single or in a relationship does not determine our ability to live well, and with virtue. It does not, consequently, determine our ability to feel safe, secure, and whole within ourselves. Our feelings of true contentment with our life are directly proportional to our success in behaving with virtue; in this respect, by itself, being in a romantic relationship is just as likely to be hindering as it is to be helpful. The conditions that allow us to love and to be loved simultaneously are relatively narrow. Throughout the entirety of our lifespan, these occasions come and go, as fate allows it, but our opportunities to act well are endless, and so us reaching equanimity rests exclusively upon us too, not on any link with another being.

It might occur to you at this point that loving as a Stoic sage would seem to equate to feelings of neutrality towards another, as the paragraph above suggests. You might think that it is a bit harsh, and I would agree. Indifference as commonly defined (i.e. lack of interest, concern, or sympathy for another) is not what the Stoic sage would aim for in their acceptance of love. A careful appreciation of what is given to us, but with no expectation that it should forever be granted to us, is what I would expect a Stoic sage to do.

As confirmed in biology , the opposite of love is indeed not hate, but indifference. This might perhaps also serve as a caution that signs of indifference for another person are not evidence of Stoic love, but rather just apathy in disguise. If a loved one is indeed nothing more than an indifferent in the Stoic sense, I say aim to make it a preferred one, one which aids both parties in the development of good character.

DESIRE & CONTENTMENT

Love as experienced by the sage would be one devoid of desire of any kind – a preferred indifferent. They would recognise that a desire to be loved can sometimes supersede the act of loving, causing us, in our most intemperate moments, to ache for the receipt, rather than focus on the offering, of love. The latter is in our control, but the former is not. Awareness of this, and that receiving affection is a gift, rather than a constant undeniable right, is important here – realising that while we might want for things to go our way in any given relationship, we should be cautious of placing our sense of happiness, or rather peace of mind, on what is at the end of the day, an external. Whether we are loved in the way we would want to be loved, or rejected and distanced from, these actions do not belong to us.

“Every individual can make himself happy. External goods are of trivial importance and without much influence in either direction: prosperity does not elevate the sage and adversity does not depress him.” – Seneca, On the Shortness of Life

Being content on your own ensures that living with another only accentuates love as a gift, and not as a necessity. Given how strongly the Stoics feel about aligning all of their goals, actions and lifestyles to the highest virtue, it is safe to assume they would rather stay single forever than knowingly be in a relationship that doesn’t align with the greater good. Although it is a thought that might seem sombre at first, we can hopefully see however how a choice over what partner to have, or even if we should have one, is as important as any other life-changing decision. When selecting our partners then, we should aim to reason with our impulses, and target interactions that are likely to pair well with our wider life choices. In particular, long-term relationships should be results of exercises of reason (whether prompted by initial impulses or not), as opposed to a nonchalant assent to sporadic moments of elation that we have little control over.

CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

In many ways, love can be thought of as a gift – one we sometimes receive without asking or reciprocating. Stoic love is the gift that keeps on giving. By nurturing ourselves and the ones we claim to love in a rational way, we encourage the betterment of everyone. Improvement of character is at the heart of Stoic pursuits, and what is true love if not supporting those you love in their quest for that improvement? Acting within the bounds of reason when infatuated is a difficult task, and requires practice before we can really perfect rationality within this context.

Working on our character before pursuing (and during) a relationship (of any kind) will allow us to see the ‘view from above’ – as we develop, and particularly as young adults, we may struggle with our identity changing, with discerning what our character may benefit from or not, and fail to see the more important things we should be directing our efforts towards. In this process we first must posit ourselves and more specifically our ego, in relation to the wider community; it is only after doing so that we can love in the true Stoic sense, that is, once our management of emotions, attachments, desires is analysed and habitually trained upon.

Simultaneously, we should recognise that character development is a lifelong process, and that in this journey that is both individual and shared with those in our lives, there needs to be compassion, forgiveness and acceptance of others’ journeys as well as our own. Mistakes will be made, changes will take place, but if we approach a loving relationship with these attributes in mind, we give ourselves and those we love the permission to be – that is, to act in accordance with nature, and with what fate has in store, while polishing up individual character traits.

Final Thoughts

Love in itself is not a virtue, as it can manifest in unhealthy or irrational ways. However, it can be imbued with virtue in the ways discussed, and refined as a virtuous act through rationality. As dealing with emotions can put this to a test, there are two practical supplements to this inquiry into Stoic love I’d like to leave you with:

-

Physical description of things as advised by Marcus Aurelius – Marcus urges us to remember what things really are when breaking them down into the parts that make them. In this case, remembering that love manifests through the medium of neurotransmitters like serotonin, oxytocin and dopamine flaring up our brains’ reward systems, can help us view our romantic situations, whatever they may be, truly from above, as a natural phenomenon and a product of our minds interpreting the world and our interaction with it.

-

In their article, the School of Life outline what ‘emotional scepticism’ is:

‘remaining highly cautious around our instincts, impulses, convictions and strong passions. It’s not that we should hate and despise these, just remain conscious of how easily they are distorted and how readily they deviate from the best understanding of our own true interests. […] Aware of our proclivities to error, we were never to rush into decisions, we were to let our ideas settle so they could be re-evaluated at different points in time and we were to be especially vigilant about the impact of sexual excitement, tiredness and public opinion on the formation of our plans.’

A clearly Stoic take, a healthy dose of emotional scepticism can be the key to Stoic love, and an antidote to more dangerous derivatives of mania possibly leading to obsessional possessive attitudes and the associated behaviours. This is reflected in Seneca’s ‘On Anger’ too, which warns against irrational emotions.

Taking the view from above once our initial first impulses and emotions have subsided allows us to differentiate between what is truly good versus appealing. Thinking of love though the Stoic lens serves as a reminder that life’s beauty, value, and our pursuit of the greater good are not dependent on temporary emotions.